Border Conflict in Africa: Part 1 — Hala’ib

Abudigana Al-Tahir

Despite centuries of conflict, death, and tragedy, coverage of issues in Africa has often been ignored, oversimplified, or excessively focused on limited facets. Deeper analysis, background, and context has often been lacking, so despite what looks like constant images of starving children in famines, and news of billions in aid arriving to Africa from generous donor countries, background context and analysis is usually missing.

In this series, a more in-tune view of Africa as a continent will hopefully be brought to light, detailing its conflicts with impartiality, and helping readers make an informed opinion afterward.

Introduction

The African continent still suffers numerous conflicts and border disputes between its different countries, despite the departure of colonists decades ago. One of the reasons, after a more in-depth look, you would find that borders that were drawn up by the colonial overseers were not influenced by history or by tribe, but by arbitrary speculation and racial stereotypes they had of Africa’s demographics.

These conflicts have caused the loss of millions of lives, in addition to their enormous economic cost in a geographical area that suffers from poverty and disease, despite its richness in natural wealth, especially oil and minerals of various kinds.

The Hala’ib Triangle:

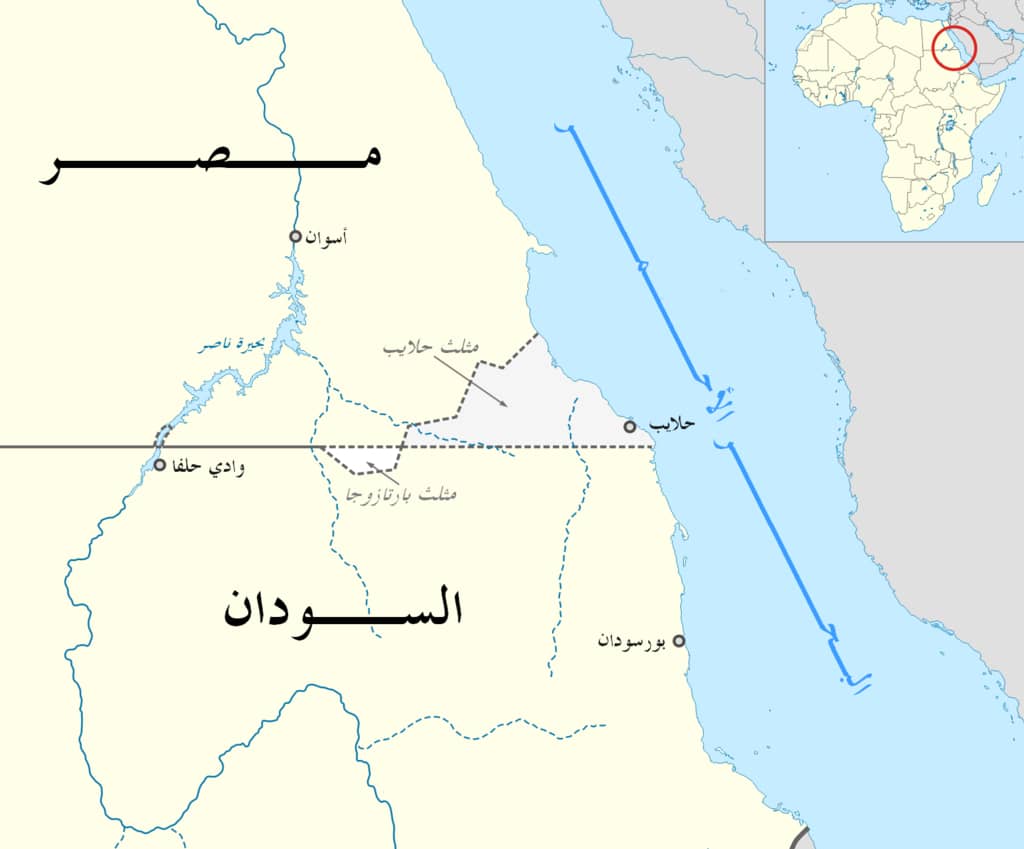

Hala’ib (Arabic: حلايب) is a port town of the Red Sea located in the Hala’ib Triangle; a twenty thousand square kilometer area in dispute between Sudan and Egypt, The area disputed being a triangular-shaped region surrounding it. The town is considered to be in the Red Sea State by the Sudanese and in the Red Sea Governate area by the Egyptians.

The area, which takes its name from the town of Hala’ib, is created by the difference in the Egypt-Sudan border between the “political boundary” set in 1899 by the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, which runs along the 22nd parallel north, and the “administrative boundary” set by the British in 1902, which gave administrative responsibility for an area of land north of the line to Sudan, which was an Anglo-Egyptian client at the time.

With the independence of Sudan in 1956, both Egypt and Sudan claimed sovereignty over the area. Egypt had sent many troops there over the years trying to gauge the Sudanese response then soon after gaining the moxie to do more. The area has been considered to be a part of Sudan’s Red Sea State and was included in local elections until the late 1980s.

Through those days the Egyptian government sent many troops to the area as a show of force, with Sudan sending more than one complaint to the Organization of African Unity with complaints of 39 military and administrative attacks.

Then in 1994, the Egyptian military moved to take control of the area as a part of the Red Sea Governate, and Egypt has been actively investing in it since then. Egypt has been recently been vehement in rejecting international arbitration or even political negotiations regarding the area.

In January 1995 Egypt rejected a Sudanese request for the OAU Foreign Ministers’ Council to review the dispute at their meeting in Addis Ababa. Then, after an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak when he arrived in Addis Ababa to attend the meeting, Egypt accused Sudan of complicity, and, among other responses, strengthened its control of the Halaib Triangle, expelling Sudanese police and other officials.

But things changed slightly after the Egyptian uprising of January 2011. The unanimity of the Sudanese with the Egyptians in their revolutions against the Mubarak regime brought the two societies closer. The Egyptian and Sudanese governments both acceded to pressure from the Nubian community and opened two land crossings between the countries, as they had been connected only by Nile ferries before then.

Egyptian completion of border road construction to the border was repeatedly delayed during the term of Mohammed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. With A Morsi advisor later concluding this was because the military held the responsibility of putting the finishing touches on construction and had no incentive to do so while Morsi was in office, given its under-wraps conflict with the Brotherhood.

After the first border crossing was opened in 2014, and the second following in 2017, both governments began speaking of plans to open a third crossing as well as linking railways and power stations. Eventually, those proved to be empty promises, as Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi and the current Egyptian government pursued policies that have hindered full normalization, with increased militarization of the border region to assert Egyptian sovereignty over the disputed Hala’ib triangle and to bolster the regime’s image as the bringers of a strong Egyptian state. This has limited the flow of people across the border, increasing distrust between Egypt and Sudan.

Both governments have also made visas for citizens of the other country difficult to obtain, further exacerbating tensions. With these restrictions, there was a meteoric rise in smuggling and illicit border crossing methods, threatening both regions with more crime and even a newly thriving drug trade.

In such an atmosphere, the idea of opening a third border crossing and integrating the two countries’ railways has seemed as distant as ever.

But recently, however, the visa application process for both sides has become laxer, allowing for easier travel for citizens of both countries. And surprisingly, in April of 2020, it was announced that the first phase of linking Egypt’s electricity grids to Hala’ib had been completed.

Nevertheless, the general volatility in bilateral ties has only added to the economic difficulties of marginalized communities on both sides of the border, while also adversely impacting the (both) Egyptian and Sudanese economies.

Hope can only be strung in the coming years to improve the situation in Hala’ib, if not for the sake of the two countries’ faltering economies, then for the minorities being displaced to this day from their original homelands.